Latest News

Jan./Feb. response: A Love for Learning

Giving helps Colegio Sara Alarcón put high tech spin on Methodist education.

by Nile Sprague with Audrey Stanton-Smith

As a young child, Citalli Crespo loved taking things apart.

“I started … playing, and then I would assemble it again,” the 14-year-old student said, laughing. “I started, like, ‘how does this work?’ And then I would take it apart. And there were times that I couldn’t do it again. And they said to me, ‘Can you? Can you repair it?’”

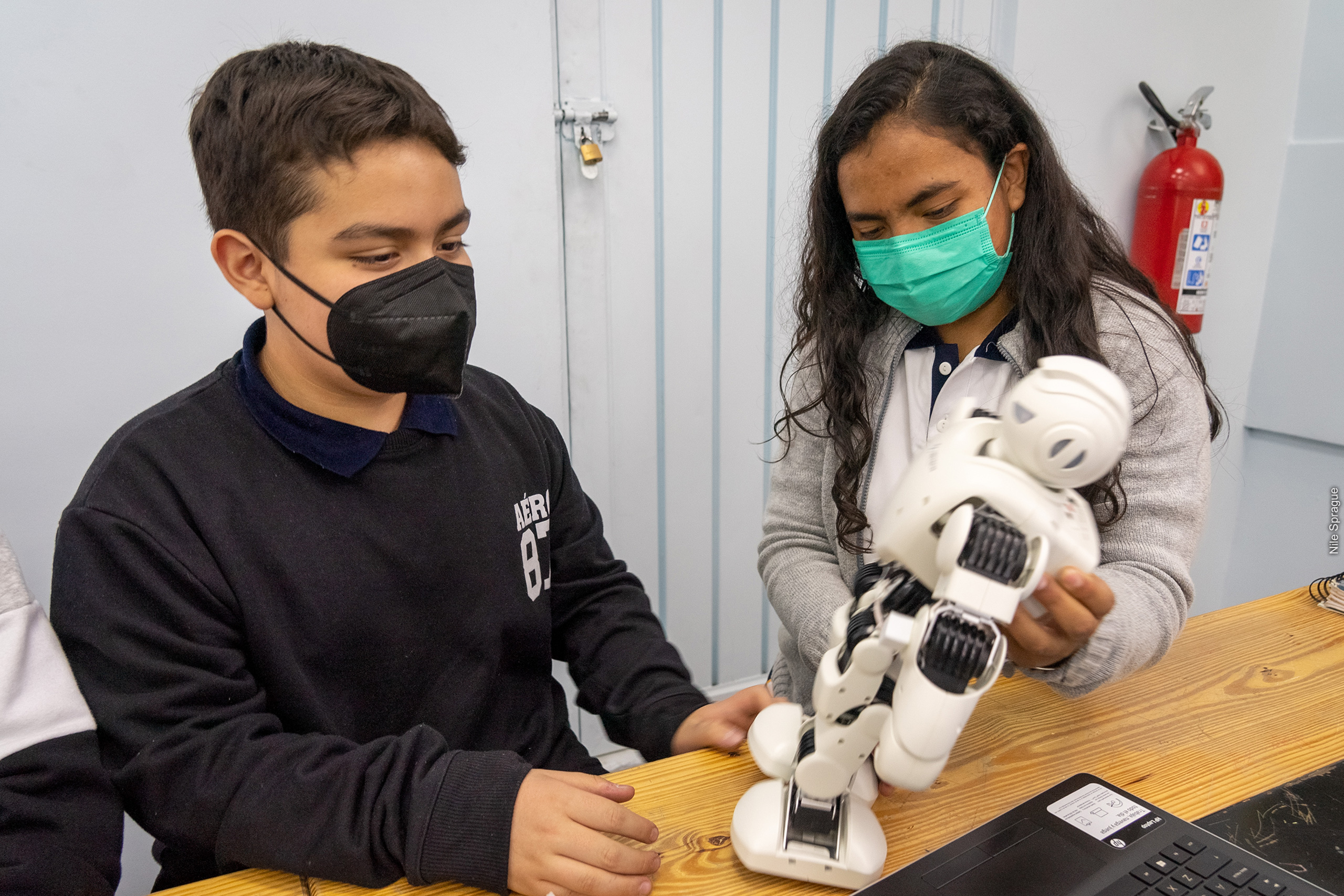

Sometimes Crespo could put things back together on her own, and sometimes she needed help from her parents, both engineers. These days, Crespo enjoys using that same curiosity in her robotics class at Colegio Sara Alarcón, where funding from United Women in Faith has helped the bilingual school purchase five humanoid robots that Crespo and her classmates are learning to program.

“We are in a competitive world,” Principal Edgar García said. “And our students in general in Mexico City use technology or these kinds of robots when they are in high school, or in the university or college, and we don’t want to wait too much time to do it.”

So, he explained, at Colegio Sara Alarcón, students begin using the robots during what Americans would call the first year of middle school. First, they program their robots by dragging and dropping graphic blocks on a computer screen, stacking one command onto another. As the students advance, they use computers to create the coding that programs the robots.

“The humanoid robot is easier to manipulate because it is more intuitive,” robotics teacher Edgar Isaí Hernández Silva explained.

For aspiring professional soccer player Fernando Alcázar, the robots are not only intuitive, but they also combine three things he loves—the workings of the human body, math, and physics.

“They are like math and physics both together,” said 13-year-old Alcázar, who appreciates what he’s learning about human mechanics from the robots. “We have to look at the [physics] laws so you can make the robot work, or math, so you can know the values about every component. … So it’s very interesting for me.”

His classmate, Yelitza Santana, views them as a possible first step toward achieving one of her dream jobs.

“I really like the robotics,” Santana said, “because, well, one of the things that I want to be when I am older is an astronaut. So, in robotics, you will learn how to program them, and I think it’s something related to the thing that I want to do.”

The same class uses other technology, she explained. Earlier in the year, they completed an assignment involving building small cars and connecting circuits to make them drive on black lines drawn by the students. They’re also working with a 3-D printer, which helps their inventions come to life.

This isn’t the first time Colegio Sara Alarcón has found itself adapting to the future and career needs of its students. Computer programming technology is just one of the many steps this school has taken over its long history.

A century of adapting

For more than 100 years, the Sara Alarcón school, in the Granada neighborhood of Mexico City, has been adapting to the needs of its students and their communities. Born from the educational missionary work of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States, the school got its start in 1874 and was officially founded in 1910.

United Women in Faith’s Mission Giving continues to support operations and programming at the school.

One hundred years ago, Mexico City was not the booming metropolis it is today, and the school initially served a rural area, García explained. Missionary Laura Temple founded it as an Industrial School in 1910, offering basic education, home economics, and classes in baking, laundry, and fruit preservation—all geared toward helping young women obtain employment in addition to receiving primary and secondary education.

But over time, factories replaced farms, the city grew, and the school found itself changing to meet the growing needs of the community around it.

“Thus, the college arises, with clear principles, in accordance with the official guidelines of the educational policy of the country, the social needs of the moment, and the foundations of the creation of the Methodist schools of providing educational service to the most unprotected classes, contributing with the government to provide education for change, combat the high rate of illiteracy, and spread culture in general,” an English translation of the school’s website reads.

Colegio Sara Alarcón now offers private education from the preschool level into the college level for some 750 students in person and online. García explained that in Mexico, many families choose to send their children to private schools. Students interviewed for this article cited the school’s convenience and quality of English curriculum as reasons for choosing Sara Alarcón.

Although it is private, García said Colegio Sara Alarcón is more affordable than other private schools and it offers scholarships so that students with varying financial needs may receive a quality education.

“We have a whole spectrum of students,” he said. “Someone can come here to the school in a taxi, because the father is a taxi driver. … Some live with a widow without a father. Some are living in these poor neighborhoods … or someone with a lot of money. So it’s difficult to know where you are coming from, because we are using uniforms, and we treat the students in the same way. But we have fathers with a good position in their companies, managers, but at the same time, we have people who use the bath in the corner when they go home.”

In fact, García said, roughly 400 students at Sara Alarcón receive some sort of scholarship based on academic merit and financial need.

“I want to say thank you,” he said, addressing United Women in Faith, “because you do make it really possible to do what we have done. And the first time that I saw the robots, I was very happy. … Our students will receive the benefit. Maybe now, but maybe in the future, because someone is helping us.”

“You can count on them”

United Women in Faith may be helping the school, but it’s the help within its hallways and classrooms that keeps students coming back. Every student interviewed said bullying does not exist at Sara Alarcón.

“I didn’t have any trouble with anyone,” said Santana. “I feel so comfortable here with the people in our community. They really listen to you. … You can count on them. … They are so supportive of you.”

That support, the students said, comes from teachers as well as from other student.

“The teacher told us about the story, and we have a conversation—not just to say it and read it,” Alcázar said, noting that his previous school leaned toward a teaching style full of many assignments with little discussion. “Here, it’s not just to read and write.”

Fourteen-year-old Iñaki San Juan, whose favorite subjects are math, chemistry, and English, agreed.

“This school? I like it very much,” San Juan said, noting how much easier it is to learn when students respect one another and teachers do more than give problems and answers. “I like the way I can participate because … I understand.”

Parents notice the positive atmosphere, too.

“So I feel that since the moment you see your son laughing or the others laugh, you see him or her satisfied, content,” parent Rocio Chavez Hernandez said. “You see them at 100 percent, so everything says your kids are happy here.”

Silva, the robotics teacher, said he sees students cooperating and learning from one another in the classroom. Female students often help male students in a field traditionally dominated by men, but all of them respect one another.

“The people who have the best performance in my workshops are the women, despite the beliefs of many of them, that engineering is more for boys,” Silva said, noting that he still has more male students than female students.

Even those students who may need help because they come from other nationalities find the help they need at Sara Alarcón.

“The community is pretty inclusive,” Crespo said, “because we have had some classmates that are from other countries: Kenya, China, Korea, Brazil.”

García said Sara Alarcón students represent some 20 different nationalities, and Crespo said English is the best way for them to talk to one another.

“When they are new, we come and someone says I will translate to him what the teacher is saying in Spanish class or in the other classes that he doesn’t understand,” Crespo said.

It’s this type of cooperation that García says makes him happy.

“We are proud of the students that are in our school,” he said. “We are different from the rest of the students from other schools. Because they are good, good students. They have good values. They have good manners. When you are going and you see them, they say, ‘good morning’ and ‘good afternoon,’ ‘thank you.’ … They grow in a different environment from the rest of the schools, even private schools, so we are proud of that.”

“There is a relationship”

Part of the “different environment” may have to do with the school’s Methodist roots, although the affiliation isn’t obvious.

“We can’t,” García said, explaining why the word “Methodist” was nearly absent from the school’s promotional materials. “It’s for the government rules. It is prohibited.”

García explained that legal restrictions prevent non-Catholic Christian schools in Mexico from openly proclaiming their faith in advertisements and signage.

Still, he said, Colegio Sara Alarcón is allowed to inform parents of prospective students that it is Methodist, which it does. There is even a pastor.

Pastor José Luis Oyoque was appointed to the school in August 2021.

“I had never been a chaplain before,” he said. “I had other different roles, but never the chaplain, so that made me a little bit nervous. But I said, ‘Okay, if that is where God is sending me, that’s where we go,’ and thanks to God, here we are.”

Oyoque said he treats the school as he would a church. He schedules visits to the sick and makes himself visible and accessible to students.

“I try to be very natural, not to force a situation,” he said. With teachers, Oyoque offers prayer. He even sends a morning devotional text to the staff. But with students, he must wait until they open those doors.

“When I have the chance to talk with one of them, almost always, they are the ones who approach this topic,” he said. “[They say,] ‘You are the one who believes in God, right? Because you look like some sort of priest.’ And I [say], ‘Yes.’ And then they start to ask me ‘and who is God?’ or, ‘Why is it that the Bible says this?’ or, ‘Why is it that my parents believe this but I do not believe this?’ And that is like the door, the entry door to talk with them about their spirituality.”

Oyoque pointed out that the school’s logo is a reference to the Church.

“The letter S is … like a symbol of the Holy Spirit,” he said, “so there is a relationship.”

Garcia believes the Holy Spirit was already at work at Colegio Sara Alarcón before Covid hit. The school had been offering hybrid education with some classes online and others in person for more than a year before COVID temporarily closed the school.

The school lost revenue but survived by cutting its budget and praying, Garcia said. When it reopened, teachers began teaching in-person and online simultaneously.

Santana is a student who prefers in-person instruction, especially when it comes to something as challenging as robotics. She admits the class is also helping her learn patience.

“If you approach things as a patient person, you can have what you want,” she said.

Nile Sprague is a photojournalist based in California. Audrey Stanton-Smith is editor of response.