Latest News

March/April response: A Gift for General Conference

Native American United Methodists share their art and faith with the 2024 General Conference.

by Mary Beth Coudal

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in the May/June 2020 issue of response magazine, written before the 2020 United Methodist General Conference was delayed to 2024. A few updates have been made to the story.

Lay pastor and nurse Diana LaRocque created more than one thousand beaded pins to share with participants at the United Methodist General Conference, a partnership with United Women in Faith to include the pins in the conference’s registration bags. LaRocque was from the Choctaw Nation, one of the many diverse nations of the Native American people who are praying for and with The United Methodist Church through their artistry during this upcoming General Conference. LaRocque passed away in July 2020.

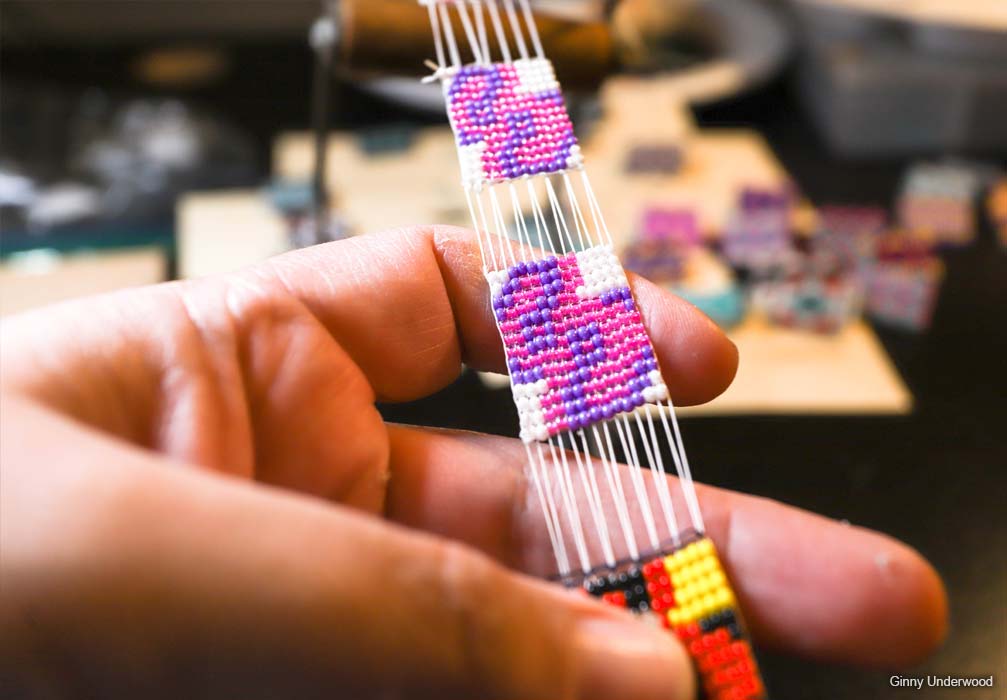

More than 6,000 beaded pins poured in from United Methodist artists like LaRocque and Native American partners from all over the country in the leadup to the scheduled 2020 gathering. Every box that arrived to the United Women in Faith National Office is chockful of beautiful beadwork. The pins serve as a reminder of the big-heartedness and deep worth of Native Americans to the larger United Methodist family.

The pins have been safely waiting in Corporate Secretary Susan Moberg’s office, collected by her predecessor Vidette Mixon, who retired in 2020.

United Methodist Women member Glenna Brayton, a Choctaw tribal member from Oklahoma now living in Colorado, invited nearby Navajo artists from the Utah/Western Colorado District Committee on Native American Ministries to contribute to the work on the pins. Thousands were loomed from people all over the region. Each pin is unique.

“I learned this from my mother: if you give something away, it has to be new,” said Brayton.

The colors may represent different themes or emotions, according to member Patsy Eyachabbe, from Wister, Oklahoma, who attends one of the 87 churches of the Oklahoma Indian Mission Conference. Each pin contains a symbolism: “Yellow’s the sun. Blue’s water. Green’s the earth.”

As in any art, there are different levels of expertise and complexity. The beading of these Native American pins is similar to the type of beadwork that adorns moccasins, regalia, and earrings. The completed object has a value greater than the sum of its parts.

“They make something out of nothing,” Brayton said.

Connecting to God and one another

LaRocque also beaded Choctaw dresses and men’s Choctaw ribbon shirts. In the community she shared her faith.

“As a vendor, people stop and talk to me, and it’s then that I can be a witness, share the Bible, hear their stories, and pray with them,” she said.

Bishop David Wilson, former conference superintendent of the Oklahoma Missionary Conference, says that the time and place of General Conference fits perfectly with the gift, “a reminder of the connectedness of the people of God. In Native thought, we are all connected, around the world, and through the circle of life.”

LaRocque shared a folk story from the Chippewa Indians in Minnesota of how art has the power to heal. Children who were beset by nightmares called on their mothers who then sought the counsel of the village elders for spiritual help.

“After a time, the answer came to make a dreamcatcher from the things they had or had access to: willow tree limbs, bent or rounded (the earth is round); web, made from limb to center. As the spider web catches the dreams, good dreams go through the dreamcatcher and bad dreams or nightmares are caught and dissipate with the morning sun.”

LaRocque shared this story, as she made and sold dreamcatchers. Her creative dreamcatching and storytelling led her, too, to interpret dreams using a biblical or Hebraic translation to people to whom she sold crafts.

Eyachabbe contends that the Christianity of Native Americans is often overlooked.

“Hello! We’ve survived a lot, and we love Jesus. We’re here for you. We’re generous people and giving of our talent.”

About the many artists, Eyachabbe says, “They love the Lord. They’re doing it out of love. They put their spirit and love into the work.”

The artists were compensated for their time and work.

Building family

Daryl Junes Joe is governance chair of the United Women in Faith Board of Directors and has served as the national language coordinator in the New Mexico Conference and on the churchwide Act of Repentance Committee.

“We include everyone as family,” she said. When Junes Joe, a tribal Navajo Nation prosecutor, had been assigned to represent children in delinquency or dependency cases in court, she always saw the children as her own children.

Several years ago, Junes Joe traveled with a United Methodist delegation to Norway, where she met Sami elders, Arctic people, who reminded her of her own family.

“As Native Americans and Indigenous peoples, we believe that we are all relatives. We address one another as brothers and sisters, regardless of religion. When we meet elders, we refer to them as mother and father. Our language has a lot of compassion.”

The United Methodist General Conference is a gathering of United Methodists from around the world—a family reunion of sorts. The beaded pins can serve as a reminder of this connection to one another, made by the hands of someone who considered the pin recipient to be family.

The international United Methodist connection was, in fact, the inspiration for the project. Mixon, retired corporate secretary for United Women in Faith, was on a volunteer trip with United Women in Faith partner Shared Interest to South Africa, where she witnessed local women making beadwork. Why not invite Indigenous women in the United States to create the gifts for General Conference in order to help economically empower them?

After all, Mixon reasoned, when United Women in Faith members gather, they always lift up the Native American people upon whose land they meet. And partnership is more than just acknowledgment.

Many of the artists and United Women in Faith members thanked Mixon for this idea and legacy. The idea came naturally to her, Mixon said, because previous to her work with United Women in Faith she was the director of corporate responsibility at the agency that is now Wespath, where she advocated for and held companies to high standards regarding their work in Israel/Palestine, South Africa, and the United States.

“I appreciate the ways United Women in Faith members are advocates for Indigenous women,” said Mixon.

The legacy of the gift to the General Conference is simple, according to Wilson.

“My hope is that people will see the pins to remind people of our presence in the church and the gifts and contributions we make to the church and the world.”

Mary Beth Coudal is a teacher and writer in New York City.