Latest News

Sept./Oct. response: Restoring Waters

Addition to Minnesota NMI Provides Homes and Health

by Paul Jeffrey

When Sheree Volesky was homeless, she lived in a tent in the woods until someone stole it. She couch surfed at the homes of relatives and friends, eventually wearing out her welcome. She lived in an ice fishing shelter, constantly chopping wood so she and her half-blind dog Archie would stay warm. When she finally got an apartment, she was evicted after a former boyfriend kicked in the front door.

Being unhoused in Minnesota was just one of the difficulties Volesky faced. She wrestled with mental health challenges that put her in the hospital three times. She has a neck injury following repeated assaults from a male partner. The resulting pain got her hooked on pain pills. She only got off the pills when she switched to alcohol.

Volesky called women’s shelters whenever she could, but they were always full. And then she called Emma Norton Services in 2024, just as the agency was inaugurating Restoring Waters, a new housing complex in St. Paul’s Highland Bridge neighborhood. They had an apartment available, and a staff person drove to pick up her and Archie.

Bridge neighborhood. They had an apartment available, and a staff person drove to pick up her and Archie.

“It was amazing. Walking in the door it felt comforting. Homey. Most of the time it’s quiet. Archie and I stayed up most of that first night because we couldn’t believe it. I had a soft bed and didn’t have to sleep on the ground with evergreen cuttings for cushioning. After having nowhere to go for so long, it was a relief. We’d been in the woods and we’d been on the streets, we’d had nowhere to go when it was cold. We’d spent the previous summer in a tent. We were tired. For the first time in a long time, I felt safe. It was a blessing,” Volesky said.

More than a year after moving in, Volesky is still feeling blessed.

Courtesy Emma Norton Services photo archives

“We’re all unusual people here. We’re all unique and all special. And we all have some things going on, whether it’s addiction or abuse or mental health issues. I can’t ask for better people to live among. We might all be a hot mess at times, but we all deserve to be here. We all deserve a chance,” she said.

Volesky has made the best of her chance.

“Because I’m living here, I quit smoking, I quit drinking, I quit everything. And not because we’re a treatment program. It’s the cooking classes and the nature-based therapy and the art classes and all that. It keeps me busy and keeps my mind focused. I’ve been through some hard times in the last 10 years, but I’ve overcome a lot. And, best of all, I’ve now reestablished a relationship with my daughter,” she said.

Methodist Roots

Emma Norton was a wealthy Minnesota philanthropist and Methodist women’s leader who in 1917 gave a gift to The Woman’s Home Missionary Society—what would later become United Women in Faith—to start the Methodist Girls’ Club, a place where young women from the countryside could live for a while when they migrated to the city in search of work or education.

Courtesy Emma Norton Services photo archives

Over the decades, it transformed itself to meet changing needs, in 1967 opening a building near the state capital. Dubbed the Emma Norton Residence, it served a variety of people, including deaf students and families with loved ones in long-term care at Regions Hospital.

As Minnesota’s unhoused population grew in the 1990s, Emma Norton Services turned its focus to helping homeless women who experienced mental health or chemical dependency challenges. In addition to the 50 women housed in the Residence, in 2002 it added Emma’s Place, a townhome community for 13 families in need.

Starting in 2017, faced with a growing waiting list at the Residence, Emma Norton also helped women secure safe housing with private landlords. These women usually couldn’t obtain housing on their own because of criminal backgrounds, a lack of rental history, or simple economic difficulties. The organization partnered with them, negotiating with the landlord, making sure the rent got paid, providing the wraparound services that would assure that the renter had what they needed to succeed. (See “Life on the Rebound” in the September 2011 edition of response.)

In the last decade, wear and tear on the Residence became a growing problem, and its isolated location in the urban landscape left women feeling stranded amidst impersonal office buildings.

“We began spending more money on building maintenance than programming, and our case managers were fixing toilets rather than working with our clients,” said Shawna Nelsen-Wills, the agency’s advancement director.

After years of dreaming, planning, fundraising, and finally construction, in April 2024 Emma Norton opened Restoring Waters in partnership with Project for Pride in Living, a local nonprofit, and the Ryan Companies, a Minneapolis-based real estate developer.

Located on the site of a former Ford plant, Highland Bridge is a mixed-use neighborhood along the Mississippi River, combining residences, offices, retail spaces, and parks in a walkable, sustainable environment. At its heart is Restoring Waters, a four-story building with 60 apartments that are currently home to 55 women and five men. Twenty-seven of the women moved from the old downtown facility, and Emma Norton staff worked with county officials to identify the others. All have experienced long-term homelessness and also face mental health and/or substance abuse challenges. Two residents have children living with them, and Nelsen-Wills said they expect that number will increase with future residents. Several residents are parents or grandparents who now have a safe home for kids to visit.

Healing Design

It’s no ordinary apartment building, however. Planners relied heavily on trauma-informed design principles, encouraged by a survey of Emma Norton staff, residents of the old facility and community partners that produced 371 suggestions for the building’s design.

Photo by Paul Jeffrey.

According to Mary Barnett, the project’s main architect, the suggestions helped create a design that would “reduce stress, depression, and spatial disorientation, while at the same time fostering an environment of social support. These psychological attributes are achieved by creating views to the outside, access to nature, and providing adequate daylight and ventilation.”

Barnett said she attempted to “provide building users with a sense of control, not only of their physical environment, in terms of temperature control and lighting control, but also control of their social space, giving residents multiple pathways throughout the building, for example, so they could choose to opt into or out of social interaction. Trauma-informed design principles focus on a sense of safety and healing, of home, of order and stability, with logical wayfinding in order to avoid confusion and uncertainty.”

Besides apartments, Restoring Waters includes a variety of activity rooms. There’s a shared kitchen for cooking classes, a meditation space, a fitness room, and a play area for children.

Photo by Paul Jeffrey.

There’s an art room where residents take painting classes, producing artwork for their apartments or simply to express themselves and heal. Restoring Waters kickstarted that process by collaborating with Art to Change the World, a local nonprofit organization, commissioning 23 local artists who met with the residents early on, asking them what colors and themes helped them feel good. They produced a series of paintings, and each resident chose one to hang in their apartment. Several of the artists now teach biweekly art classes at Restoring Waters.

“Most of our residents moved here with nothing more than a backpack. Although we provided them with quality furniture, their walls were blank. Having their own artwork helped them feel at home. And it’s theirs to keep. When they move, they can take it with them if they want,” said Nelsen-Wills.

a garden area. Photo by Paul Jeffrey.

Restoring Waters also has a plant room where residents can cultivate plants for their rooms. And residents are transforming a rooftop patio into a comfortable green space with trees and other plants.

The focus on plants is not accidental, and Restoring Waters enlisted Cynthia Berlovitz, a nature-based therapist with the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, to help residents develop their green thumbs.

“Our big goal is to build community and help people learn how to take care of the environment around them, how to nurture things as they nurture each other, share responsibility and have fun together,” Berlovitz said.

“There’s a hormone that your body releases when you are taking care of a plant or taking care of an animal. It’s similar to what a breastfeeding mother experiences. That hormone provokes a feeling of trust, well-being, belonging, connection, and reduction of fear. That’s good for all of us.”

Restoring Waters resident Sherril Brown says working in the sensory-rich plant room has helped her.

“Every plant is different, so I have to pay attention to what I’m doing, what kind of light they like, how often they need watering, and which ones need fertilizer,” Brown said. “Plants create mindfulness in me.”

Restoring Waters also features Emma’s Corner, a small store with household and hygiene items, clothing, and a variety of other things donated by supporters. Residents can purchase them with Emma’s Bucks, a currency they earn by attending community gatherings, participating in classes, doing community chores, and meeting with their case managers.

Volesky says she loves Emma’s Corner.

“I love it. Because I didn’t have any money, that’s where I bought my daughter’s Christmas gifts,” she said.

The Living Room

person in The Living Room, a healing space connected to Restoring Waters, a housing

project in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Photo by Paul Jeffrey

Another unique feature of the housing complex is a comfortable lounge off the lobby of Emma Norton Services’ new headquarters, which shares the new building with Restoring Waters.

Called The Living Room, it’s an innovative model of mental health care that reduces hospitalizations by providing peer support in a calming environment.

According to Lauren Daniel, Emma Norton’s clinical director, the space pairs people in mental health crises with peer support specialists who can relate to their stresses and hardships, and connect them with medical and other community resources as needed. It’s designed to help people before their crisis becomes a real emergency. Clients don’t need insurance and don’t need to meet any clinical criteria to qualify for support. They don’t even need to give their real name.

Some crises do require medical intervention, but Daniel says most can be addressed by peers who have earned state certification through training and experiencing mental illness themselves or in their families.

“Our peer support specialists are people with experience of mental health or substance use disorders who are living well in their own recovery journeys. Our goal is to divert people away from the emergency department when they’re experiencing mental health crises. Because when people in crisis do go to the emergency department, it’s loud and often overwhelming. They often get turned away because of long wait times, or they don’t meet the criteria for inpatient care. So we’ve created a warm and welcoming environment where people can get immediate support and de-escalation,” Daniel said.

“Our specialists are there to be a coach, a role model, a beacon of hope. You’re not sitting across from someone with a lot of letters after their name, which can be really intimidating. Instead it’s someone who can say, ‘I’ve hit rock bottom. I know what this feels like.’ Or, ‘When I had my first panic attack, it was really scary. Here are some tools that helped me.’ They’re not therapists or counselors, but they can provide coaching, mentoring, coping skills, whatever one-on-one support that’s needed in the moment.”

Tonya Brownlow, Emma Norton’s executive director, says the concept was pioneered in the Chicago area by the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

“People come with a wide variety of questions and struggles. Some might say, ‘I don’t have a therapist and I don’t even know what it’s like to go and find one.’ Others might say, ‘I’ve never taken medications, and I’m wondering how that works.’ Or others could say, ‘I don’t have housing right now and I’m in an abusive relationship. Can you give me resources?’ In all of those cases, we can help. But the underlying goal is to help that person through whatever stress or mental health symptoms are preventing them from moving forward in their day,” Brownlow said.

Rose Nelson is a peer support specialist in The Living Room.

Photo by Paul Jeffrey

“I’ve struggled with my mental health my whole life,” said Nelson, who had a successful career in IT but kept wrestling with mental health challenges that she says weren’t diagnosed correctly. After one episode led to her hospitalization, she knew something had to change.

“Once I got out, I knew that I wanted to do something different with my life. It wasn’t fulfilling in the ways that I needed it to be. When I found this position, it felt like just the right fit. I applied, was accepted and went through the training, and it’s been fantastic. I get to use my empathy every day. I get to support people in a nonjudgmental way. I get to see people for who they are and relate to them through my own life story. I get to help people in a way that uses my strengths,” she said.

Nelson believes The Living Room and professional therapy are complementary.

“There’s the clinical approach, people who see things technically and prescribe medications that may be needed. I know I need medications to manage my mental health. And with peer support, you can talk with someone who’s really been through it, and who offers support in a nonjudgmental space, sharing pieces of their story to help you feel more comfortable with what’s going on in your life. It’s something the therapist can’t offer,” she said.

“We offer a safe and nonjudgmental space for people to be themselves, to express what they need to express in the way that they need to express it. Sometimes that involves anger or frustration or sadness or some other extreme emotion, and it’s helpful for folks to have a place that they can go to express those things.”

After it opened late last year, The Living Room had 143 visits during the first three months. Only one of those led to a hospital referral, but the peer support specialist arranged for the client to pass quickly through the emergency department and be settled in an inpatient room within 30 minutes.

In coming months, the program is expanding, adding more peer support specialists and offering telehealth visits. It’s reaching out and attracting more clients from outside Restoring Waters, yet residents have remained the principal users. And many of them say it’s been a big help in their personal journeys.

“We all need help at times, and it’s comforting to know there’s somebody there for you. Sometimes you need to talk, but you don’t want to talk with a family member or a friend, and you don’t want somebody in the building to know your business,” said Volesky.

“There’s no shame in getting peer support, and it helps you realize that you’re not the only one who struggles with certain things. Having somebody there who has been through it, it’s easier to talk to them than to somebody who thinks you’re an embarrassment, who wants to judge you. It doesn’t matter if you’re rich or poor, if your face is full of acne or you’re starving to death. Everyone deserves to have someone to listen to or talk with.”

Brown wrestles with several mental health challenges but credits the peer support program with helping her cope.

“When I’ve seen a psychiatrist, they spend a lot of time writing stuff down, and there wasn’t a lot of feedback other than them saying, ‘Hmmm,’ before they gave me some fancy diagnosis and prescribed some medicine,” she said.

The program isn’t strictly limited to The Living Room, which consists of four tan walls, a faux fireplace, and some comfy chairs. Brown says one peer support specialist, in order to help her relax and talk freely, took her walking in a nearby park. And when she ran out of food, another specialist brought her a bag of groceries.

Supportive Housing

Photo by Paul Jeffrey.

Brownlow says the wraparound services provided by Restoring Waters grow out of a realization that homelessness has many roots.

“There was a time when we talked about the homeless as somebody who’d had a house fire or missed a paycheck and lost their housing. It was a temporary crisis. But now we’re 50 years into that temporary crisis. We’re dealing with generational homelessness, and even if we get someone into housing, that’s just the first step. We often have to work through years of untreated mental illness or trauma from violence in their lives,” she said.

“We’ve also made the situation worse with a chronic lack of affordable housing. You can’t blame homelessness simply on mental illness or chemical dependency or substance abuse, because there are a lot of wealthy people who have those same issues, but they don’t end up homeless. Affordable housing is in short supply in most places, and people’s incomes are not rising as fast as housing prices.”

Brownlow says supportive housing solutions like Restoring Waters are not inexpensive, but they’re cheaper than the alternative. She says Minnesota politicians of all political stripes have adopted housing first as a best practice in setting public policy.

“They’ve come to realize that it’s more cost effective to put someone into housing rather than have them remain on the streets and in the shelters, where society has to pay for expensive emergency services, and people never achieve stability and security,” Brownlow said.

“Housing is a public health priority. People who experience homelessness have serious health disparities. So the more people we can get into housing, the more we reduce strain on our health care systems and on safety systems like police and emergency responders.”

Brownlow says cultural expectations—for example, that the poor can pull themselves up by their own bootstraps—quickly fall apart on the streets of U.S. cities.

“We too often think that if we can just give people a little help, they’ll respond and recover. But for many that won’t work, because being homeless has become a full-time job of its own. You can only be at a shelter from 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. So during the day, you walk around the city and figure out where you can be, and where you can find a bathroom. You need to figure out your meals. You’re supposed to show up at a government office and make sure all this paperwork is in. You’ve got to spend your whole time just existing, yet we expect people in that situation can easily change their lives. They can’t, often because we’ve created too many barriers,” she said.

Brownlow says Restoring Waters is designed to remove those barriers by providing housing first.

“We have given people a dignified place to live. And we often hear visitors say, ‘You’ve made it so nice. What’s going to make them want to leave?’ But our goal is not for them to leave. Maybe they will get to a point in their lives where they don’t have to live here anymore if they don’t want to, but if they need to live here, it’s here for them. It’s not about moving on, it’s about creating a sense of home,” she said.

Women Prayed It Through

United Women in Faith has helped create that sense of home ever since the Methodist Girls’ Club opened its doors over a century ago.

Women from local United Methodist congregations are among the sponsors of Birthday Bingo, for example. Those are monthly gatherings where residents—who often have no close family—celebrate the birthdays of those who live in the building. Playing bingo yields prizes donated by church groups, including gift cards for local stores.

Although everyone who plays is guaranteed some sort of prize, Volesky says that despite the presence of “the church ladies,” the game can get rather heated.

Emma Norton Services. Photo by Paul Jeffrey

“We are nuts about bingo. I’ve never seen a group of people go so crazy about bingo, including some that are a little crazier than others. We’re all friends but we play with enthusiasm. It’s great,” she said.

One of those stalwart church women is Shirley Jackson, a member of Northeast United Methodist Church in Minneapolis. A retired educator, she has supported Emma Norton for more than four decades.

“In those early days, before Emma’s Place when we were just a small agency with a dorm in the middle of the city, things weren’t always easy. We were on the edge of closing several times. I believe that it was United Methodist women who prayed it through,” she said.

“If it weren’t for those women, Emma Norton and Restoring Waters wouldn’t be here today.”

Jackson says the women’s circles in her congregation were always ready to help.

“We supplied whatever they needed, things like blankets, toothpaste, and soap. We came to Emma Norton and made Valentine’s cards with residents. One group came and did a weekly Bible study,” she said.

“We’ve also watched as Emma Norton has changed over the years. It started out sort of saving people, people who were pretty needy. Now it’s much more about empowering people, supporting them as they develop their skills and whatever they need to be independent.”

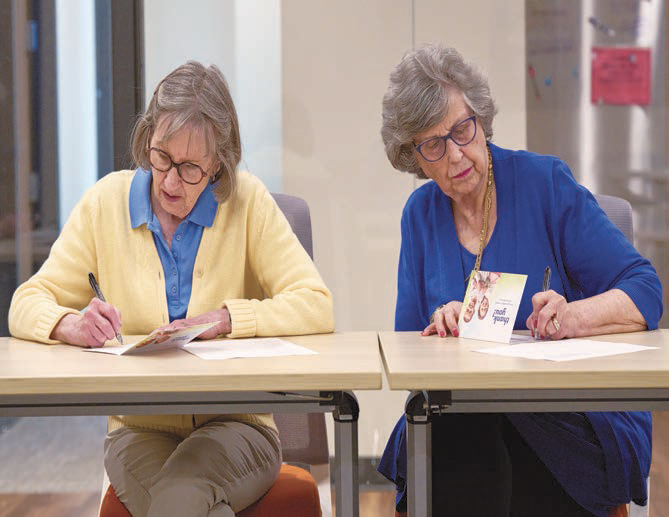

Ann Girres (left) and Shirley Jackson, both members of the board of directors of Emma Norton Services, sign thank you notes to people who have donated to Restoring Waters, a housing project in St. Paul, Minnesota, for women and others who are homeless and also wrestle with mental health and/or substance abuse challenges. Girres is president of the board. Both women are members of United Women in Faith and long-time

supporters of Emma Norton, which sponsors Restoring Waters.

Photo by Paul Jeffrey

As people started moving into Restoring Waters, many United Women in Faith members got the rooms ready, stocking kitchens and bathrooms with all the small items that made residents quickly feel at home. Jackson said people from her congregation continue to come to play bingo and provide other support to the residents. “We have their picture on our wall at the church. We talk about them as being part of our church,” she said.

Emma Norton remains a National Mission Institute of United Women in Faith, and Brownlow says the group remains a vital supporter.

“They’re always here volunteering, raising funds, fighting for donations, doing whatever is needed. It’s so good to have folks who support what you are trying to do in a world that doesn’t always appreciate it. But they are more than just a kind of auxiliary that provides money and labor. They are also advocates for people experiencing homelessness. They’re engaged with the issues and the people, which makes them incredible ambassadors to state government leaders and local community leaders and neighbors to build the awareness that homelessness is just not acceptable in our communities,” Brownlow said.

One of several United Women in Faith members on the Emma Norton board of directors, Jackson was awarded the agency’s Heritage Award at its annual dinner this year.

At the same dinner, Emma Norton awarded its yearly Champion’s Award to both the Minnesota Annual Conference of The United Methodist Church and the conference’s United Women in Faith. Brownlow said the two “long-time faith partners … have been champions of Emma Norton for over 100 years.”

Accepting the award for the conference, Bishop Lanette Plambeck recalled the founding of the Methodist Girls’ Club in 1917 and noted the similarities between the original Emma Norton’s time and today. She pointed to the beginnings at that time of the Great Migration of People of Color leaving the segregated South, the Espionage Act of 1917 that curbed civil liberties and dissent, the women’s suffrage movement that led to the 19th Amendment three years later, and the public health crisis that contributed to the 1918 Great Pandemic.

“Those days aren’t quite behind us. But Emma Norton believed that the church had a responsibility beyond the sanctuary walls. She said we must not wait for the world to change. We must begin the changing,” Plambeck said.

The bishop said Emma Norton’s challenge to the church remains just as important today, and is being lived out in the ministry of Restoring Waters.

“Dignity is not earned, it is inherent. Housing isn’t a reward, it is a right,” Plambeck said. “Healing is not a privilege, it is a promise. And transformation is not a service that we give to people, but something we do in community.”

Paul Jeffrey is a freelance photojournalist and founder of Life on Earth Pictures. He lives in Oregon.