Latest News

Nov./Dec. response: Remember Sand Creek

The Sand Creek Massacre Is Not Just Cheyenne and Arapaho History, It Is Methodist History

by Tara Barnes

Photo: Mike DuBose/UM News

On the morning of Nov. 29, 1864, U.S. militia soldiers attacked a settlement of Cheyenne and Arapaho encamped at Sand Creek in Colorado Territory.

The attack was a surprise for many reasons. The officer who led the attack did so in secret, unbeknownst to other officers. The settlement was a chief’s village, which meant it comprised mostly women, children, and elderly. And perhaps most disturbing, the peoples camped at Sand Creek were promised safety under U.S. military protection.

Yet as Chief Black Kettle raised an American flag alongside a white flag of truce, U.S. Colorado Volunteer soldiers attacked the peaceful camp, killing 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho, most of them women and children.

This attack was led by a Methodist pastor, who was enabled and defended by a prominent Methodist governor. This massacre is not just Cheyenne and Arapaho history. It is not just Colorado history or U.S. history. It is also Methodist history.

Forgive Us Our Trespasses

In August 1864, Governor John Evans proclaimed that all Native Americans in the Colorado Territory who did not relocate to specified U.S. military bases would be considered hostile and would be “pursued and destroyed.” He authorized all settlers of Colorado to then “go in pursuit of all hostile Indians on the plains,” giving vigilantes permission “to kill and destroy, as enemies of the country, wherever they may be found.”

Evans was a physician, politician, railroad promoter, and governor of Colorado Territory from 1862 to 1865. He was also the territory’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs and a devout Methodist. He’s a founder of Chicago’s Mercy Hospital, Northwestern University, and the University of Denver, which started as the Methodist Colorado Seminary. Northwestern too began as a Methodist institution, where professorships still bear his name. Evanston, Illinois; Evanston, Wyoming; and Evans, Colorado, are named for him, as is Evans Avenue in Denver.

Mount Evans, however, is no longer named after him. It became Mount Blue Sky in 2023.

The Horse Creek Treaty, also known as the Fort Laramie treaty, in 1851, secured parts of what are today Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas, and Nebraska as Native land. Colonialist settlers, however, continued to ignore Native land rights, especially after the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush in 1859.

“A hundred thousand of them streamed across our lands, searching for their fortune,” said Dr. Henrietta Mann, Southern Cheyenne, during a 2014 Smithsonian forum on Sand Creek. “They made a road so wide—I’m told it was about two miles wide—that no Buffalo would cross that bare, denuded land.”

Though the Cheyenne chiefs were always at the table of peace, peace was an impossibility she said, considering the constant illegal immigration and settlement on Native American lands.

“Trespassers, essentially. Trespassers.”

When Cheyenne and Arapaho defended their land, the U.S. military would retaliate, which Mann described as a “very vicious cycle of brutality.”

Mann is a descendent of Sand Creek survivors and attended the 2016 United Methodist General Conference to hear the report on Sand Creek and assist The United Methodist Church in its repentance to the Cheyenne and Arapaho people.

“We were land barons,” she said with a slight smile during the panel, “which is so tragic when you stop to think of the small remnants of land that we’ve managed to hold for ourselves.”

By 1861, in continuous attempts at peace and survival, Cheyenne and Arapaho had ceded all of the Rocky Mountain front range, per the Fort Wise Treaty (a treaty noted as illegitimate by Cheyenne law but nonetheless used and ignored as desired by the U.S. government), relinquishing the land once guaranteed them by the Horse Creek Treaty to the settler colonialists.

Evans became territorial governor less than a year after the Treaty of Fort Wise and the start of the U.S. Civil War. His ambition was to see Denver (and his political career) grow. Convinced that the Cheyenne and Arapaho were conspiring war against the White settlers, he spent much of his time begging civilian and army officials for a military solution. The largest regiment that attacked Sand Creek was formed just three and a half months prior to the massacre.

In its study of its founder’s role in the Sand Creek Massacre, the “University of Denver John Evans Study Report” stated the following: “Evans’s action and influence, more than those of any other political official in Colorado Territory, created the conditions in which the massacre was highly likely. Evans abrogated his duties as superintendent, fanned the flames of war when he could have dampened them, cultivated an unusually interdependent relationship with the military, and rejected clear opportunities to engage in peaceful negotiations with the Native peoples under his jurisdiction. Furthermore, he successfully lobbied the War Department for the deployment of a federalized regiment, consisting largely of undertrained, undisciplined volunteer soldiers who executed the worst of the atrocities during the massacre.”

“While not of the same character,” the report stated, “Evans’s culpability is comparable in degree to that of Colonel John Chivington, the military commander who personally planned and carried out the massacre.”

The Fighting Parson

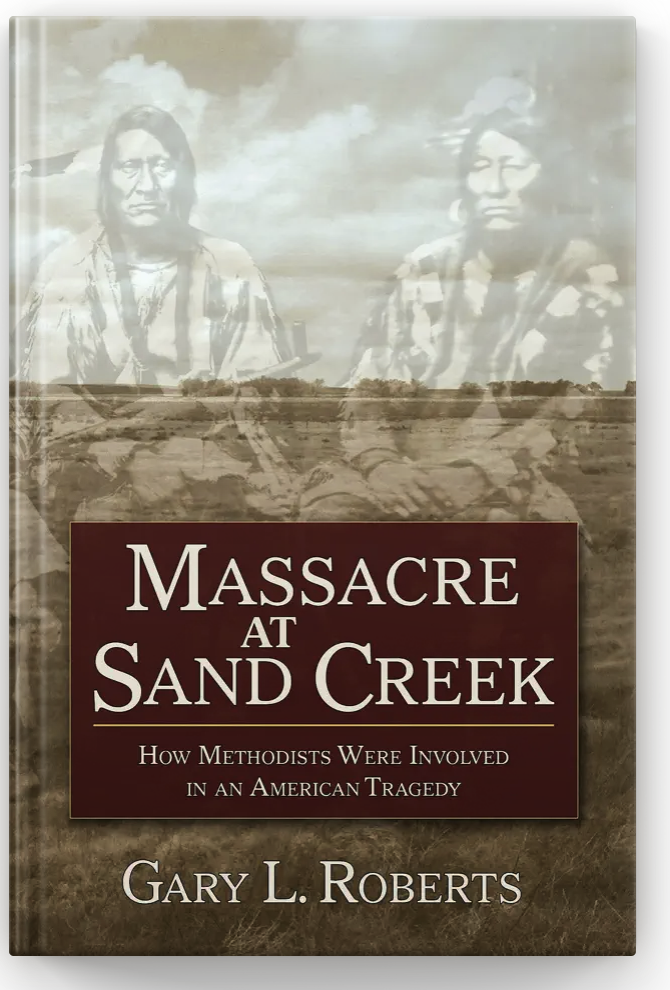

Colonel John Chivington was known as “the fighting parson.” A convert to Methodism in the early 1840s, he became a licensed exhorter, or lay preacher, in Ohio in 1844 and by 1852 was ordained an elder in the Missouri and Arkansas Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, as historian Gary Roberts explains in his book Massacre at Sand Creek: How Methodists Were Involved in an American Tragedy. Chivington was the mastermind of the brutal massacre and carried the title of Methodist minister into the slaughter of women and children, of widows and orphans under the protection of their chiefs and of the United States of America.

Like Evans, and the founder of Methodism John Wesley before him, Chivington hated slavery. In fact, it was his defense of his abolitionist views that earned him his nickname, after he faced pro-slavery members of his congregation by arming himself in the pulpit with a Bible and two pistols. Like Evans, and the founder of Methodism John Wesley before him, Chivington was also a mechanism of Manifest Destiny, a racist notion of supremacy that gave White Christians permission to settle and conquer where they decided God had taken them.

Photo by Joey Butler, UM News.

Dr. Ashley Boggan explains in the Sand Creek video series produced by the General Commission on Archives and History that after spending time with the Muskogee (Creek) peoples of Georgia, Wesley came to view Native Americans as fully human. In this Evans and Chivington did not follow suit.

Chivington rose in popularity as a preacher in the Denver mining camps in 1860 and even more in 1861 as he donned a Union Army uniform as chaplain and recruited soldiers for the U.S. Civil War, rising in rank (though often behaving as if his rank were higher than granted), traveling himself to Washington, D.C., in pursuit of the title of brigadier general (which he did not receive, even with Evans’s endorsement).

After Evans’s August 1864 proclamation on how to deal with the “Indian problem,” Chivington declared martial law, forcing all men in Denver to enlist in the military.

“Chivington reveled in his newfound power,” Roberts shares in his book. Chivington abused his power and manufactured stories of Native American attacks to maintain an excuse for martial law and to sow fear.

In May 1864 Chivington wrote to Major Edward Wynkoop, “The Cheyennes will have to be soundly whipped before they will be quiet. If any of them are caught in your vicinity kill them, as that is the only way.” Per testimony of then U.S. attorney general for the Colorado territory, Samuel Browne, Chivington told a Denver crowd that his policy toward the Native Americans was to “kill and scalp all, little and big,” he said, for “nits make lice.”

Michael Straight, journalist and author of A Very Small Remnant, a novelization of Sand Creek, wrote about the massacre for The Denver Westerners Monthly Roundup in April 1963, calling Chivington “a man of violence,” “a fanatic,” who “had little moral scruple” and “did not hesitate to use any means that served his ends.” Yet in command of Colorado regiments and ordained in the Methodist Episcopal Church he remained.

Cold-blooded Massacre

Nov. 29, 1864, is known as the deadliest day in Colorado history. It’s also a day that changed the Cheyenne and Arapaho forever, for more was lost than just the 230 people murdered. The massacre led to the permanent removal of the Cheyenne and Arapaho from their homeland, a trauma that continues to be passed down through the generations.

“Sand Creek—it severed our ties and our connections with the land, with the animals, with the plants here in this area,” said Halcyon Levi, a member of the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribe, in a June 2024 story from KUNC. “We were forcibly brought to Oklahoma following Sand Creek.”

On dawn that cold November morning, on the barren land on which the U.S. government had relegated the Indigenous peoples seeking peace and safety, encamped Cheyenne and Arapaho woke to the sound of hooves on the ground. At first some thought it might be buffalo. When they saw it was instead a military cavalry, they thought the army had arrived to bring rations or maybe word of where to move next, as Fred Mosqueda, tribal historian for the Cheyenne and Arapaho, explains in a 2024 interview with History Colorado’s Lost Highways series.

“Instead, they were fired upon,” he said. “They were destroyed as they stood there.”

Chivington would claim that Sand Creek was a fortified camp full of warriors ready for battle, but multiple eyewitness and survivor accounts contradict this. No one at Sand Creek was standing guard or on lookout. The horses were not near camp. Many of the younger men who were at the camp were away hunting buffalo. The volunteer cavalry lost only 12.

In his UNUM episode “Remembering the Sand Creek Massacre,” filmmaker Ken Burns explains how the massacre was recast as a heroic battle.

“This was not a battle,” Burns says. “This was a cold-blooded massacre, committed by citizen soldiers, enabled by federal policy, and fueled by racism.”

Blanche White Shield was a Cheyenne elder and descendant of Sand Creek massacre victims. In her oral history recorded as part of the founding of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, she talked about the role of Cheyenne chiefs.

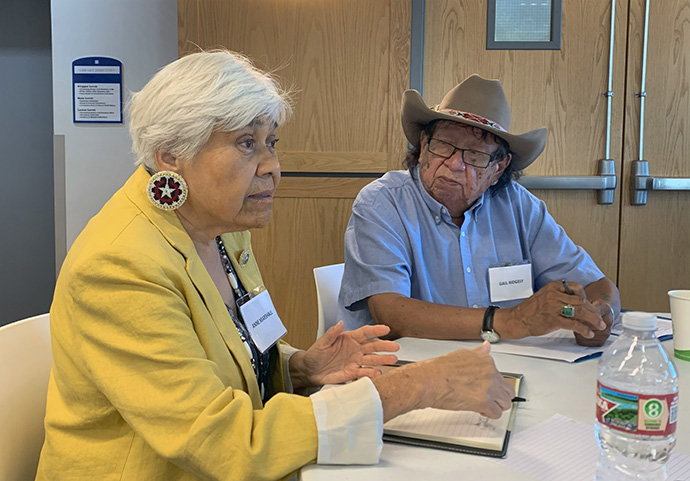

Cheyenne and Arapaho (Oklahoma), and Great Plains Bishop David Wilson speak at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver in September of 2024.

Photo: Joey Butler/UM News

“They said that some old magic chiefs, they really want make of peace with all of it,” she said. “They don’t like to cheat. Once they become chiefs, they got to be honest. They got to be sincere and love their people and help them in good ways. Since they’ve become chiefs, they can’t argue with anyone. If somebody hurts them, they’ve got to take their pipe and smoke, that’s all they could do.”

Cheyenne chiefs Black Kettle and White Antelope didn’t run to get firearms or weapons when the army descended. They ran to get the white flag. It was the chiefs who waved the flag, White Shield said. Chief White Antelope was shot dead as he waved his hands asking the soldiers to stop.

White Shield’s story is featured in the Colorado History exhibit: The Sand Creek Massacre—The Betrayal that Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever.

Once fellow soldiers at nearby Fort Lyon figured out Chivington’s plan, they pushed back. Chivington threatened them, and he lied about the real plan of Sand Creek.

Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer and their companies were present at Sand Creek, but they refused to participate. Three White men in the village tried to stop the attack as well but were pushed back. There was no doubt even in the moment of the attack that what was happening was an act of evil.

“The sun delivered death that morning,” writes Cinnamon Kills First, a Northern Cheyenne author, filmmaker, and beadworker, in her essay “My Relatives at Sand Creek” on her blog CinnaDocuTell. “My relatives opened their eyes to the sounds of gunfire, howitzer cannons, and spooked horses. They ran for their lives. Mounted soldiers chased them down. The outnumbered Indian men tried to defend themselves and their loved ones with firearms and arrows. Scattering, many women and children escaped up the creek. Mothers found a bend in the river a mile north and hid with their children there. Brothers and sisters, trained not to cry, held each other in silence while their bullet wounds bled.”

(Official White House Photo by Cameron Smith)

The indiscriminate slaughter of unarmed women, children, and elderly continued all day and into the next. As their tents burned, many who survived the day succumbed overnight to exposure or their wounds. The next day, the soldiers returned to mutilate the bodies, keeping body parts as trophies. Two-thirds of those killed were women, children, and elderly.

“As if victors to a valiant battle, the troops marched back to Denver and proudly paraded into the city displaying scalps and flesh. (It’s even been said that troops later used the scrotum of Indian men as pouches for their tobacco.),” writes Kills First. “Yet, the image of Native Americans in the historical American psyche is ‘heathen’ and ‘savage,’ and it’s easier to cling to this than to learn how to hold the truth.”

What Came Next

Chivington fashioned himself a hero and called the attack God’s will, and the “battle” was celebrated as such in local newspapers. In of the news stories Chivington described Sand Creek as the “most bloody and hard-fought Indian battle that has ever occurred on these plains.”

However, the victory parade was short-lived. Accounts began to be shared of what really happened on November 29, notably from Soule and Cramer, whose private and official correspondence spoke of the atrocities that occurred. Soule called the soldiers who took part in the murders “cowardly” and “a perfect mob.”

In his December 1864 letter to Major Edward Wynkoop, Soule shared some of the horrors he witnessed that day. Be warned that the following quote will be very hard to read.

“I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized. One [woman] was wounded and a fellow took a hatchet to finish her, and he cut one arm off, and held the other with one hand and dashed the hatchet through her brain. One [woman] with her two children, were on their knees, begging for their lives of a dozen soldiers, within ten feet of them all firing—when one succeeded in hitting the [woman] in the thigh, when she took a knife and cut the throats of both children and then killed herself,” he wrote. “Some tried to escape on the Prairie, but most of them were run down by horsemen. I saw two Indians hold one of another’s hands, chased until they were exhausted, when they kneeled down, and clasped each other around the neck and both were shot together. They were all scalped, and as high as half a dozen taken from one head. They were all horribly mutilated. One woman was cut open and a child taken out of her, and scalped.”

Cramer’s account corroborated Soule’s, and joined other reports beginning to reach high officials. Meanwhile, the soldiers continued to be cheered. The press still celebrated the “battle” and the gruesome “trophies” were still publicly displayed. Those seeking to hold Chivington and Evans accountable, however, were easily able to find soldiers who were ashamed to have been part of it. Some of the more truthful reports were also starting to be shared in the press. An investigation is ordered. Soule is murdered a few months after testifying. Evans was removed from office and resigns in disgrace. Chivington retires from the military less than two months after the massacre and never faces charges.

The Council of Forty-Four, or the council of chiefs, lost many members at Sand Creek, causing a rift in Cheyenne order, Roberts says, with new soldier chiefs coming to power.

“Only a few whites understood the reasons that Sand Creek was so important,” Roberts continues. “It was, first of all, a massacre, but more than that, a slaughter that taught even the most peacefully inclined that whites could not be trusted. Few officials, if any, understood that Sand Creek was a chiefs’ village. It was an experiment that all of the Cheyennes and Arapahos were watching. Practically, it was a chance to prove the white man’s intent. It was an experiment with the potential to have brought peace to the central plains. Instead, Chivington’s attack eliminated virtually every voice for peace among the Cheyennes. Trust was broken. The white man had proven the value of his word.”

Where Was the Church?

Though the U.S. government sought the truth, the Methodist Episcopal Church and Methodist Episcopal Church, South, did not. Roberts explains that the church considered Sand Creek more of a distraction, trivial in the face of the U.S. Civil War.

“What stands out most strikingly in the Methodist response to Sand Creek and the events that followed … is: indifference. Sand Creek was simply not important enough to the Church to matter.” The reports of Sand Creek were disturbing not so much for the massacre itself but that it may damage the church’s reputation.

Six Colorado ministers wrote a letter in support of Chivington. Bishop Calvin Kingsley used his influence to (unsuccessfully) help prevent Evans’ removal as governor. The Methodist paper the Northwestern Christian Advocate defended Evans as not responsible and Chivington via disbelief, vowing to help Chivington clear his name. When met with criticism while preaching in Kansas, Chivington himself asked why, then, does the Methodist Episcopal Church not cut him off?

After Sand Creek, the Colorado Conference did not readmit him, nor was he immediately readmitted to the Nebraska Conference, but he was regularly preaching after the massacre. Nebraska did certify him for preaching again in 1868. When he returned to Colorado in 1883, it was as a hero. When he died in 1894, he was given a grand funeral with full Masonic rights at the Trinity Methodist Episcopal Church in Denver. Mourners paid their respects for almost an hour after the funeral. He was lionized in his eulogy by the Methodist pastor. He stood by Sand Creek until his dying day.

A petition to the 1868 General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church to be in mission with Native Americans was tabled indefinitely, and it stayed that way until President Ulysses S. Grant created a Board of Indian Commissioners in 1870 and invited Methodists and granting the Methodist Episcopal Church 14 Native American mission agencies, underwritten by the government. It lasted only until 1882, and the Methodists, Roberts notes, were considered “the least engaged and least successful of all denominations.”

Methodists did operate Indigenous boarding and day schools beginning as early as 1801 in Georgia, another history the church is currently exploring.

Boggan says, “It took 132 years for the United Methodist Church to begin to even acknowledge Sand Creek.”

Where Is the Church Today?

Diane Marsden first heard about Sand Creek in 2008 at a United Women in Faith retreat in Montana focused on the mission study Giving Our Hearts Away: Native American Survival. A Cheyenne woman spoke to the group about Sand Creek.

“Hearing about what happened there, and the atrocities that took place, it broke my heart and brought me to tears,” she said in a video produced by the Mountain Sky Conference about the Sand Creek Spiritual Healing Run. She became friends with woman who spoke and has built a relationship with her family. “It has been an honor to have this relationship with the Cheyenne people and learn about their culture,” she said. Marsden in a member of the Native American Committee of Sheridan, Wyoming.

Photo by Joey Butler, UM News.

In 1996, the United Methodist General Conference passed the petition “Support Restitution to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma for the Sand Creek Massacre” and offered an apology to the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples, doing both without fully consulting those most affected. A service of reconciliation was also cut from the proceedings.

In 2008, the General Conference committed $50,000 to a research center at the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site with the resolution “Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site support.” In 2012, an Act of Repentance was held, and delegates passed Resolution 3324, “Trail of Repentance and Healing.” The Council of Bishops and the General Commission on Archives and History committed to providing a full disclosure of Chivington, Evans, and the church’s involvement in the tragedy. The task force commissioned Roberts to do this work.

In May 2016, Roberts offered his report to the General Conference, the same month his book Massacre at Sand Creek: How Methodists Were Involved in an American Tragedy was published by the United Methodist Publishing House. This book was featured on the 2017 United Women in Faith Reading Program as well. The General Conference also passed Resolution 3328, “United Methodist Responses to Sand Creek,” in which United Women in Faith is named.

“Trail of Repentance and Healing” and “United Methodist Responses to Sand Creek” were supported by the 2024 General Conference and remain official work of The United Methodist Church.

In November 2024, to mark the 160th anniversary of the tragedy, United Women in Faith hosted a special episode of its Faith Talks podcast focused on the Sand Creek Massacre featuring Otto Braided Hair, a Northern Cheyenne descendant, and Bishop Elaine Stanovsky, who with Braided Hair co-chaired an advisory report on the Sand Creek Massacre during the 2016 United Methodist General Conference. The podcast also featured JuDee Anderson, who worked as a high school therapist on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation and whose United Methodist church in Sheridan, Wyoming, began the denomination’s relationship with the Northern Cheyenne Sand Creek descendants.

In 2025 the church offered proceeds from Roberts’ book to the installation of a Sand Creek memorial on the grounds of the state capitol, and the General Board of Church and Society is hosting the traveling Sand Creek Massacre Exhibition this month at the United Methodist Building in Washington, D.C. The Commission on Religion and Race has approved a grant to support a historic gathering that the Cheyenne Council of Forty-Four is planning. The council has not met since 1864.

The Road to Healing

Members of United Women in Faith are women of action, but sometimes, there are no easy answers when it comes to the work of repentance, reparation, and reconciliation. Now is the time to listen, learn, and pray. Our work has only just begun.

“A question we must ask ourselves today is how were Methodist teachings used to justify such violence, and what responsibilities does the church still bear in fostering expansionist policies that led to Indigenous displacement,” says Boggan in the fourth video of Archives and History’s Sand Creek Massacre video series, donations toward which will go to support the Denver memorial. “It is not only for the massacre that we must hold ourselves accountable and repent, but also for having a theology of American exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny as components of our mission and ministry.”

Ask yourself how you have benefited from this theology and then enter into lament if you have. Lament is an important spiritual act of repentance—and hope. Theologian Soon-Chan Rah explains in his book Prophetic Lament, “Lament calls for an authentic encounter with the truth and challenges privilege, because privilege would hide the truth that creates discomfort.” Sit with the pain. Bring it to God. Wait for your call to be part of the healing.

Mosqueda calls us all to take care of one another.

“When you was born Arapaho, you know, there was certain things that happened in your life. But the main thing they taught you was always to take care of each other. And I think, if everybody, the non-natives, you know, the tribes, if they can all look at that and say, that’s how we survived, is by taking care of each other,” he said in his interview with History Colorado. “… Use that to all look at each other and say, well, we have to take care of each other if we’re going to make it. … That’s how Arapahos made it, you know, and I think that’s the thing that they should look at, because then it would be a better place everywhere if we just … take care of each other.”

Mann, who co-wrote the small-group resource On This Spirit Walk with United Methodist the Rev. Anita Phillips and was awarded a National Humanities Medal by President Joe Biden in 2021, closed her Smithsonian address with the reminder that the Cheyenne and Arapaho survived and survive.

“We remember that day. We remember that tragedy. But we also carry a collective inheritance of abundant love, profound teachings, sophisticated philosophies, and deep spirituality that were not destroyed at Sand Creek,” she said. “And without them, we would not have survived the overpowering oppression of a mighty new nation intent upon claiming everything in its path, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Our history is what it is: Heartbreaking and heartwarming. But we need to remember, however, that we are all participants on a human journey, that we walk a road of life that originated back at creation. Which includes Sweet Medicine’s great teachings and which opens us to a hopeful tomorrow. The road led to Sand Creek in 1864, but it did not end there. The Cheyenne and Arapaho … survived. And they continue to walk this road of life without end. We were not destroyed. And we continue to remember our deep attachment to land and this place that we were first to call home.”

Tara Barnes is director of denominational relations for United Women in Faith.

Select Resources to Learn More About Sand Creek

Read

Massacre at Sand Creek: How Methodists Were Involved in an American Tragedy by Gary L. Roberts, available at Cokesbury and other book retailers.

Cheyenne and Arapho Tribes website at cheyenneandarapaho-nsn.gov.

Listen

“In Remembrance of the Sand Creek Massacre” episode of United Women in Faith’s podcast Faith Talks.

Watch

Sand Creek Massacre and Methodism video series by the United Methodist General Commission on Archives and History, available at ResourceUMC.org/SandCreekMassacre.

The Sand Creek Massacre report from the 2016 United Methodist General Conference, available from the Mountain Sky Conference at vimeo.com/180080213.

You can find more resources on our blog at uwfaith.org/general-conference/2024/remember-sand-creek.